Case Studies

Case #1: The Green and Gold Incentive Program

In the early 2000’s, John Deere was several years into a lackluster attempt to enter the zero-turn radius mower (ZTR) market. Over the previous ten years, the market for commercial mowing, that is for products that professionals used to mow lawns, had transitioned from the front-mower style to the “ZTR” or zero-turn radius mower. Instead of aggressively responding as it should have, Deere had spent the last 10 years trying to sell against the new machine form. “Sell against” as in try to convince customers that they didn’t really want the new machine but that instead what they really wanted was their more expensive, larger, less maneuverable front mowers. Deere insiders were convinced that customers wanted steering wheels and would never transition to this strange-looking machine – and they were blinded to the significance of the new category’s performance advantages.

There is a great lesson in this resistance to the market’s changes. Marketing folks began convincing themselves of the veracity of their story – the more they told it to each other in the lunchrooms and water coolers, the more they believed it to be true. Unfortunately, the story ignored the performance advantages of the ZTR. Engineers were also convinced that front mowers were the superior form. If they doubted this, marketing would reassure them.

It’s a bit harsh to say that Deere completely ignored the market. They benchmarked a leading company (at the time) in the ZTR space – Grasshopper. Based on this benchmarking, Deere created an entrant to compete with the ZTR – called the F620. The F620 had a plastic hood, was very long, and was not responsive. When you pushed the control levers. it whined before slowly lurching forward.

It’s a bit harsh to say that Deere completely ignored the market. They benchmarked a leading company (at the time) in the ZTR space – Grasshopper. Based on this benchmarking, Deere created an entrant to compete with the ZTR – called the F620. The F620 had a plastic hood, was very long, and was not responsive. When you pushed the control levers. it whined before slowly lurching forward.

Meanwhile, key competitors made their machines bullet-proof – both in function and style. Heavy steel. Big bolts and welds. Solid, strong, heavy – and ready for the army of landscaper employees with varying degrees of caution who would drive them over curbs, on and off trailers, and across properties of all types. In addition to grass, they would mow sticks, rocks when not running into trees. John Deere dealers were quick to understand John Deere’s entrance into the ZTR space was a weak one. They took on new lines with names like Scag, Exmark and Bobcat. They acquired the lines that provided the products that their customers demanded.

As Deere realized that they had made an error, it licensed a competitor’s product that was tough – more like the Scag and Exmark brands that had succeeded so well. These were called the “M-Series”. Unfortunately, the momentum had already been lost. John Deere was not perceived as a ZTR player. And worse, the marketing group from Deere was still telling the same story that commercial customers would never accept a “machine with sticks” and that the front mower was destined to reclaim its status. Within this delusional environment, the popularity of the ZTR machine for commercial mowers continued to grow at ever increasing rates.

By this point, the average John Deere dealer had taken on an additional brand – so they didn’t have a problem themselves per se. . They just switched their focus from the John Deere front mower to the other branded-ZTRs and life was good. Dealers were disinterested in Deere’s product and were more than happy to sell “other colors”. A few particularly loyal John Deere dealers worked hard to sell the F620 – but it was extremely difficult. Most dealers just stocked a couple units to keep Deere corporate happy and they prayed that some poor soul would be interested in buying them.

It was at this point that I joined the commercial mowing marketing team. I worked for Dan Schmidt, the product manager for ZTRs. Dan was new in his role – and was not part of the F620 fiasco. Prior to being product manager, Dan was a product sales manager in Florida – where he worked with dealers and customers daily. He knew first hand that customers hated the F620 because it looked fragile – and its overall length made it difficult to put on a trailer. He knew that customers valued tough, durable machines. Dan was smart – and he knew the ZTR market better than anyone else in Deere’s commercial mowing marketing at that time. As he worked with engineering to develop the next generation of John Deere ZTRs – he leveraged that knowledge for every decision to be made. Every feature, every styling detail.

I learned how to be a product manager by working for Dan. He was balanced in that he was forceful but not too much – a team member pushing to ensure that the best decision would be reached. But as the one who knew the customer best, as the one who knew the market the best, he was was correctly assertive. His logic for a decision was never “because I said so,” but rather, he presented customer stories and anecdotes to support his case. After people worked with Dan for awhile, they came to trust his judgement. He knew the market and customer better than anyone. He was a great example to me in a role that I aspired to have – product manager.

It was in this environment that Dan asked me to look at our incentives as we prepared to create a new program for the next year. Essentially, it was a complex weave of $X off this product or that – with some low interest financing thrown in. Programs began and ended on this date and that- and it wasn’t clear to what degree that they even influenced the purchase because dealers had a hard time keeping up with them.

Regarding ZTR sales, a few dealers were doing well with Deere products but the vast majority were ignoring them while selling other brands. Fortuitously, I had just finished reading The One to One Future (on the reading list) which emphasized that all customers were not equal and shouldn’t be treated as such. The 80/20 rule should be applied to customers and dealers alike. The current incentive program treated all dealers equally. “Equal” meaning that we might have an incentive for a $300 rebate off a certain model, but any dealer could claim the rebate. Dan and I chatted about this quite a bit – and together, we wondered what a scenario would look like if we only provided rebates to the top dealers who were selling our product – while giving them an opportunity to earn their way in. To earn this higher status level, you had to sell a certain quantity of ZTRs. It was a different kind of plan – as Deere had a culture that insisted that all dealers should be treated the same. But quite frankly, “treating everyone the same” is poor business. Do airlines treat their customers the same? Banks? No. The best companies know who their good customers are – and provide them a higher level of service. Within the “treat all dealers the same” culture, it would be difficult to sell our idea. I would have given it less than a 5% chance at the time. But Dan Schmidt wasn’t one to be deterred by the cultural norms. A college football star at Kansas, who also had a pro football career was unlikely to be discouraged by our long odds. When we initially presented the idea “up the ladder,” after a few moments of stunned silence – we were told that our program was likely illegal – and we were then asked “How was this going to help us to grow if only a small percentage of dealers could get the incentive?” The flaw in our opponents logic was that it overvalued the value of the 1-5 units per year that the disinterested dealers were selling – and it undervalued the untapped resource with the more aggressive dealers – including those who might elect to be more aggressive with a new program to unlock their initiative. The program, as we envisioned it, would have two levels, the “Green” and the “Gold.” Green dealers would get $150 off per every unit sold. Gold dealers would get $300 off per every unit sold. They had to sell a minimum number of units to qualify for each tier. If you qualified, you got the incentive money. If not, you got nothing. As we would roll out the program, we would pre-qualify some based upon their past year of sales. Others could become eligible by selling the required minimum number of units. The message would be clear: Get on board – and join us in the John Deere ZTR business – or don’t. But if you don’t, rest assured that we’ll be spending our ZTR marketing efforts to support those who have opted in.

Regarding ZTR sales, a few dealers were doing well with Deere products but the vast majority were ignoring them while selling other brands. Fortuitously, I had just finished reading The One to One Future (on the reading list) which emphasized that all customers were not equal and shouldn’t be treated as such. The 80/20 rule should be applied to customers and dealers alike. The current incentive program treated all dealers equally. “Equal” meaning that we might have an incentive for a $300 rebate off a certain model, but any dealer could claim the rebate. Dan and I chatted about this quite a bit – and together, we wondered what a scenario would look like if we only provided rebates to the top dealers who were selling our product – while giving them an opportunity to earn their way in. To earn this higher status level, you had to sell a certain quantity of ZTRs. It was a different kind of plan – as Deere had a culture that insisted that all dealers should be treated the same. But quite frankly, “treating everyone the same” is poor business. Do airlines treat their customers the same? Banks? No. The best companies know who their good customers are – and provide them a higher level of service. Within the “treat all dealers the same” culture, it would be difficult to sell our idea. I would have given it less than a 5% chance at the time. But Dan Schmidt wasn’t one to be deterred by the cultural norms. A college football star at Kansas, who also had a pro football career was unlikely to be discouraged by our long odds. When we initially presented the idea “up the ladder,” after a few moments of stunned silence – we were told that our program was likely illegal – and we were then asked “How was this going to help us to grow if only a small percentage of dealers could get the incentive?” The flaw in our opponents logic was that it overvalued the value of the 1-5 units per year that the disinterested dealers were selling – and it undervalued the untapped resource with the more aggressive dealers – including those who might elect to be more aggressive with a new program to unlock their initiative. The program, as we envisioned it, would have two levels, the “Green” and the “Gold.” Green dealers would get $150 off per every unit sold. Gold dealers would get $300 off per every unit sold. They had to sell a minimum number of units to qualify for each tier. If you qualified, you got the incentive money. If not, you got nothing. As we would roll out the program, we would pre-qualify some based upon their past year of sales. Others could become eligible by selling the required minimum number of units. The message would be clear: Get on board – and join us in the John Deere ZTR business – or don’t. But if you don’t, rest assured that we’ll be spending our ZTR marketing efforts to support those who have opted in.

The thing is…an “incentive” should be just that. It should motivate someone to do something. In my view, the dealers that would take us to  the next level were not the ones selling five units per year. For them to double their units, we just sell five more units. But for the dealer selling 150 units per year, to double to 300 is significant. This was the idea – and it was a good one – but it would have died on my laptop screen in a jumble of scenarios created in Excel if not for the communication skills of others.

the next level were not the ones selling five units per year. For them to double their units, we just sell five more units. But for the dealer selling 150 units per year, to double to 300 is significant. This was the idea – and it was a good one – but it would have died on my laptop screen in a jumble of scenarios created in Excel if not for the communication skills of others.

It was proving to be a difficult idea to sell. Until…Dan and I got a new manager – Gilbert Pena. Gilbert was and is – awesome. A favorite person of mine. A bulldog. Aggressive. Smart. Communicates well. Enthusiastic – and NO BS with Gilbert. A straight-shooter; direct yet always kind. I would love to have his talent for being forceful and likable at the same time. He had the respect of many and was the absolute perfect person to take on the John Deere status quo and promote the Green and Gold program. Gilbert liked the program. He bought in – and became its champion.

To make it a reality, we had a fateful meeting with the executives who could approve or deny the Green and Gold program. I will never forget this meeting. It was offsite – at the Grandover resort in Greensboro, NC. The table was arranged in a U-shape – with execs all around. Gilbert took the stage and began selling. The naysayers were persistent.

“I think this is illegal.”

“It wouldn’t be fair to the other dealers.”

“We’ve never done this before. All dealers should be treated the same.”

Gilbert made the case and did not back down. His short stature was not a negative but just helped to reveal the tenacious bulldog that he was. He pointed his finger. I can still picture the U-shaped room with executives sitting all around. He paced. He would not be denied. Dealers needed to join us to promote this business. We are wasting our time working with dealers who will not promote our business – and we are not supporting the good dealers nearly enough who are ready to run with us NOW. We would elevate the status of those who’d opt in as a “Green Dealer” or as a “Gold Dealer.” As they threw out all the reasons why not to do it, Gilbert used their arrows for fuel. He came back harder and stronger each time. He wouldn’t be denied. Steve Jobs, Thomas Paine and Napoleon could not have done better.

Gilbert made the case and did not back down. His short stature was not a negative but just helped to reveal the tenacious bulldog that he was. He pointed his finger. I can still picture the U-shaped room with executives sitting all around. He paced. He would not be denied. Dealers needed to join us to promote this business. We are wasting our time working with dealers who will not promote our business – and we are not supporting the good dealers nearly enough who are ready to run with us NOW. We would elevate the status of those who’d opt in as a “Green Dealer” or as a “Gold Dealer.” As they threw out all the reasons why not to do it, Gilbert used their arrows for fuel. He came back harder and stronger each time. He wouldn’t be denied. Steve Jobs, Thomas Paine and Napoleon could not have done better.

Gilbert gave a performance that I had never seen before or since.

The Green and Gold Program was approved.

Fast forward to the next year, and the next…John Deere territory managers across the country would sit down with their dealers and make plans to qualify as a “Green” dealer. Those who were Green were planning how to be “Gold.” Those who were Gold were making plans to exploit their advantage. This created a new problem as dealers who couldn’t get enough ZTRs to sell screamed at the factories to produce more.

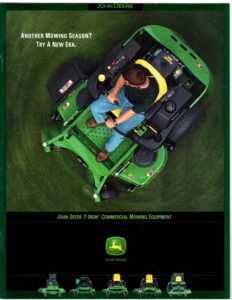

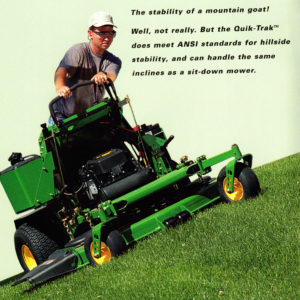

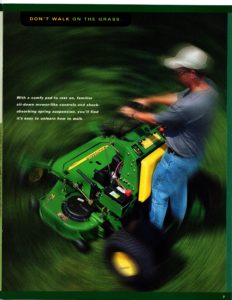

The incentive program had created a pull for new products. Dealers were in the game and growing. Along the same time, Deere’s new generation of ZTRs, the 700 series launched. Under Dan Schmidt’s leadership, they would be great products. Strong, durable, just as maneuverable as the entrenched competitors – but more comfortable. A product worthy of the “John Deere” name.

Soon after, I left marketing to become a territory sales manager in Tennessee. One of my dealers in the Knoxville region had only sold three ZTRs in the previous year. They didn’t care for the machine style – and were content to ignore the category. A dealer was required to sell 25 mowers to become a Gold. It sounded like 10,000 when you’re only selling three. Motivated by the program, and my insistence that the ZTR would continue to displace front mowers….and eventually…displace lawn tractors…it was imperative to get about the ZTR business. The dealership owner, Stuart Richie, accepted the challenge and backed it up with great leadership. He put a chalkboard in the back office where he documented their progress. When and if they hit 50 units, they would get the $300 retroactively per unit. The sales staff, the ownership and I all became quite engaged in this pursuit. It was a battle of inches, and we finally crossed the 50 threshold – just barely – late in the year. It was an exciting moment for me. Something dreamed up in my marketing job was brought to fruition by others who believed in it – and now I was able to participate first hand to see it in action as it made a real difference. The dealership went from three units per year to 30. Turns out that 30 was easy the next and in future years they would soon rocket on multiples of that. The ZTR business was established and growing under its own momentum. You’ve heard that “all politics are local” – and all marketing is ultimately local as well.

The impact everywhere in other locations was just as dramatic. As the success of the program became obvious, there were very few people who knew that the idea came from Dan and I’s brainstorming about the woes of the current dealer situation, the inevitability of the ZTR market growth, and an interesting idea in a business book. The Green and Gold Program would become a major initiative for John Deere along its path to reclaim its status a leader in commercial mowing.

By the way, that’s me in the John Deere images which were marketing materials for the new 700 series launched in the early 2000’s. My luggage didn’t make the flight with me, so everything that I’m wearing was purchased hours earlier at Walmart. I still have the jeans!

Case #2: The John Deere 1-Family (The X20 Tractor Program)

Background:

In the late 1990’s, Kubota invented a new category of compact utility tractor, the BX series. It would be called the “sub-CUT” or sub-compact utility tractor. The BX tractors were larger than garden tractors – but smaller than the smallest compact tractor. These machines could take a loader and a backhoe – and were true tractors – as opposed to the garden tractor-style which were really quite limited in what they could do. Deere responded with pretty good product, the 2210 (later updated as the 2305) for which it outsourced the manufacturing to a Japanese firm. Deere became competitive with a solid #2 market share – but the 2210’s margins were rather slim – and Deere increasingly became convinced that this was not a profitable market segment to compete in. However, they would compete anyway to keep Kubota, a tough competitor at bay. However, outsourcing the manufacturing was not consistent with Deere’s long term operations strategy. Therefore, the “X20 Project” was launched in order to create a new sub-CUT for which Deere would manufacture internally.

In the late 1990’s, Kubota invented a new category of compact utility tractor, the BX series. It would be called the “sub-CUT” or sub-compact utility tractor. The BX tractors were larger than garden tractors – but smaller than the smallest compact tractor. These machines could take a loader and a backhoe – and were true tractors – as opposed to the garden tractor-style which were really quite limited in what they could do. Deere responded with pretty good product, the 2210 (later updated as the 2305) for which it outsourced the manufacturing to a Japanese firm. Deere became competitive with a solid #2 market share – but the 2210’s margins were rather slim – and Deere increasingly became convinced that this was not a profitable market segment to compete in. However, they would compete anyway to keep Kubota, a tough competitor at bay. However, outsourcing the manufacturing was not consistent with Deere’s long term operations strategy. Therefore, the “X20 Project” was launched in order to create a new sub-CUT for which Deere would manufacture internally.

The initial two team members of the X20 project were E.J. Smith and myself. As a product manager, I would lead the strategic marketing to design a new tractor from scratch that could be built in a John Deere factory. E.J., the program manager, oversaw an immense project – tasked with the design of a transmission, front axle, styling – and many implements. E.J. Smith was (and is) the best program manager imaginable. We were attached at the hip for several years during execution of this project – and in many ways – this was the most productive time of my career.

This project had quite a few constraints from the beginning. First, Deere had determined a pre-set number of tractor platforms that it would use going forward to minimize operational costs. Next, John Deere corporate couldn’t agree on which factory should be assigned to the project. The candidates were the Horicon, WI and Augusta, GA factories. Horicon was the factory responsible for lawn and garden tractors – both marketing and manufacturing. Augusta was responsible for compact utility tractor marketing and manufacturing. Since both factories wanted the project, a special oversight team with representatives from both factories was assembled. Most of the members of the oversight committee had aspirations of ultimately getting the product to be built in their factory – so our oversight committee meetings were going to be interesting. As a business, quite frankly, John Deere had set up this project to be a colossal failure. I’ll explain this point by point:

We were told that the scope of the 2305 replacement was that we should build something very close to the same tractor – but just built in a John Deere factory instead of a supplier’s factory.

“There profit margins are always going to be small with these little tractors. This project is only about cost reduction.” was a common directive from the oversight committee. As an aspiring New Product Dog, I knew that the committee was putting too much value on NPD speed – and not enough on accuracy. That is, they were undervaluing the impact that a new feature set could deliver if the customer requirements were defined well.

The project had an aggressive schedule – far too aggressive for any serious development – certainly no time for market research.

Because the scope was just to in-source the 2305 tractor, it was believed that no market research was needed – and that the development  team should be able to work very quickly.

team should be able to work very quickly.

We were pressured by executives to spend technical resources to investigate a gasoline engine option – even though this idea had no market support. From the start, it was a management fantasy that customers would select a gas engine over a diesel engine despite a mountain of research to the contrary. We would endure harsh criticism when we made our data-driven case that demonstrated that the gas engine option should not be in-scope.

Can you see that the direction we were given was a little fragmented? There was no time allotted for market research, little time for technical development – we were directed to just directly replace the 2305 – and then we were given this little scope-destroyer to “investigate adding a gasoline engine.” Where did this gasoline engine idea come from? Executives told us that customers wanted didn’t want to keep multiple fuel types onsite. This was not based on research, but just on their assertions. Meanwhile, our market research would show that a gasoline engine would be very unpopular. The gas engine would be slightly cheaper – but not much – so while it could potentially help to offer a lower cost SKU, it was a costly add – even as an option. Here’s why: Designing modularity into a platform is not free. We would have to make concessions to the platform to accommodate both engines. “Concessions” means cost. So even X20 tractors with diesel engines would have a slightly higher cost due to design modifications made to accept both engines. Every unit…over the life of the product – this means hundreds of thousands of units would have a higher cost just to allow for the possibility of the gas engine. The gas engine was slightly cheaper, performed worse (less torque – an important specification for tractors), and would drive lots of operational costs in the form of factory inventory and overall support for an expensive component.

The scope of the project was to “in-source the 2305, 2320 and X700 on the same platform.”

This is where the oversight committee really set us up for failure. Total failure. These three machines had vastly different capabilities – and it would be a product development disaster to combine them onto one platform. (A “platform” is a common architecture from which modular components can be added to create multiple SKUs. For automobiles, this is often the chassis. It’s a strategy to cover as much of the market as possible while minimizing operational and manufacturing costs.)

What was the logic for combining the three tractor models into one platform? There were two items:

- They all used 24 HP engines.

- There was a big operational initiative to get to five total platforms for compact tractors – and the only way this could happen was to combine all three.

The X20 Oversight Committee missed a huge determinant of what should define a tractor platform – it’s not the engine – it’s the transmission. The transmission is defined by many customer requirements – but the most relevant to the reason that these three should not be combined are:

- Tire size

- Weight that the tractor can lift

Larger tire sizes stress the transmission significantly more than smaller tire sizes. It’s not a linear relationship – it’s an exponential one – so it’s not like going from a 24″ tire to a 26″ tire only changes the stresses the transmission 8% – it’s much more than that. The 2305 could lift over 50% more than the X700 and the 2320 could lift 70% more than the 2305. Dramatic differences. In order to use the same transmission, you would have to use the heaviest lift case – thus driving cost back into the units that didn’t require the capacity.

As bad as the idea was from an engineering perspective, the idea only gets worse when considering the relative sales numbers. The lowest capacity tractor, the X700, sold twice as many units as the 2305 and the 2305 sold 3X the number of units as the 2320. This means that to reap the benefits of a “common platform,” the low volume 2320 would drive significant costs back into higher volume models. I’ll supply some made-up numbers for the purpose of illustration. Imagine that the 2320 annual volume is 5,000 units. Then imagine that the 2305 volume is 15,000 units – making the X700 volume to be 30,000 units. So the “price” of the common platform is that the 5,000 2320 units would drive significant cost into 45,000 2305 and X700 models. How did the executive committee justify this? They challenged us to “find a modular approach that would make it work” to drive to a single platform. We had no choice but to keep that within our project’s scope. It was another burden, another headwind, another misguided attempt to influence the project. This was an interesting idea – but remembering that modularity is not free – and that we were not able to change the laws of physics – it was a really, really destructive complication to add to the the X20 program.

With all these “complications,” this project was like a ship placed on course with an iceberg that the leadership believed to be a lovely shiny object on the horizon. In fairness to the X20 Committee, they were set up for failure as well. There were many agendas – and they had some unwelcome oversight as well from above. I believe that most individuals were distraught about the project – but having to work with colleagues that they didn’t normally work with from other factories, it was hard for the committee to be a well-functioning team. However, likely due to the political complexity, they assigned their best people to the project. They assembled an amazing team to execute the project. And for that, despite some scope issues, they deserve a lot of credit.

The Project Begins

In my first act as product manager, I drove to Charlotte to meet with E.J. Smith. I carried my John Deere CRP (Customer Requirement Process) manual – and I had two objectives:

- To alter the project’s scope to allow for a premium model

- Get the time to execute the market research.

E.J. and I went through the CRP manual, discussed the risks, and the nuttiness of the schedule – and we left that session united in that we would present our case to the X20 Oversight Committee to add time to the schedule. And when I say “time”, I mean years. We were going to make the case to add years to the schedule. Next, regarding the addition of the premium model – a significant scope change – I had something in my favor. For larger tractors, a Sid Bardwell, John Arthur, and Kerri Jernigan had created a great marketing and new product development strategy where we would have a premium and economy model in each tractor size. This strategy did not initially include the sub-CUT however as it was believed that these smaller tractors would always be low margin. Similar to a loss leader to get people into the dealerships. The 2305 was considered to be a basic product – and nobody believed there was space to go “up-market” with new features that addressed customer needs. Though, I personally did believe there was space up-market to go. I had an interest at heart driving that belief – I knew that this major project – building a tractor from the ground up – was a unique opportunity. As an aspiring New Product Dog, I wanted the opportunity to execute all of the fuzzy front end. Market research, idea generation, everything.

E.J. and I had our scope-changing meeting with the committee – and we successfully made our case to expand the scope in duration and to include a premium model. How were we so influential? We used the fact that the committee was divided into two factories – that it wasn’t overly clear “who was in charge” to our advantage. We were able to exploit this uncertainty to get our way. I still didn’t like the other baggage that was put on the project (common platform to combine multiple tractors, gas engine, etc.) but now with the time for proper analysis – we could sort through all of that in time. We would ultimately make the case to spend more money on market research than Deere had ever spent on a non-agricultural product to my knowledge. We would ultimately spend over twice the typical amount that was being spent on a large project like this- and this spending level invited jeers which were bothersome – and added to our headwinds a bit.

With a charter in hand, the team was put together – and it was an amazing one. E.J. Smith was a superhero of project managers. John Kuhn was our technical lead – with such extensive experience in tractor and mowing technologies. The three of us with E.J. leading the project management, John Kuhn leading the technical development, and with myself leading the marketing strategy – we formed the core. A great benefit of working on a project that was sponsored by two factories, Horicon and Augusta, is that we were given the best of the best engineers. Plus, a new transmission team was assembled that E.J. would oversee. You see, Deere did not have the capabilities at the time to design its own transmission in that tractor size – this was something that was always outsourced.

We proceeded to execute a massive amount of market research. The market research was an assault involving trips all over the country to interview customers, multiple expensive surveys – with expensive data analysis on the back end. Qualitative exploratory research. Quantitative confirmation research. Conjoint studies. TURF analysis. Styling studies with art work of design concepts. Concept testing for potential new features. Focus groups with drawings complete – resulting in the consumption of massive amounts of M&Ms behind the two-way glass. Riding events where customers would try new concepts on tractors that were painted gray to eliminate any brand biases. We also tapped into other ongoing studies that could provide relevant input – getting few questions added here and there. An Outcome-Driven Innovation project on the higher level needs for “Maintaining an attractive property.”

I found a particularly rich bounty of customer insights within an under-utilized resource that we had – the Customer Loyalty Surveys which were sent to a sample of current compact tractor and garden tractor owners. Shawn Noble was running the loyalty program at the time for Deere and it was an amazing resource. I spent many, many hours reading the verbatim comments of our current customers. I coded the comments and then analyzed them for action.

I also found a rich source of data at a customer enthusiast site Tractor-By-Net. I could visit a hundred customer by reading the comments of many customers. I could see the images of what product modifications they had made. I could read about what they liked about Product A and hated about Product B. So much information at my fingertips. I embraced the investigational learning mode like a Sherlock Holmes wanna be.

For analyzing and executing this research, Deere provided top rate market researchers and analysts. Clarence Brewer, James Jeng, and Frank Maier challenged me, educated me, advised me – and I not only learned a ton – but was able to get very usable information from the market research due to their expertise and kindness (and patience!) to help me to understand.

We concluded that there were seven unmet customer needs. These were:

- Reduce the effort to change attachments

- Work in low light conditions

- Improve mowing performance

- Operate comfortably

- Mow under trees

- Carry tools

- Operate safely on hillsides

We conducted multiple idea generation sessions to address the seven needs – they carefully vetting the feature concepts with customers – both internally and externally. Here are some of the feature adds that would ultimately address the needs above:

Reduce the effort to change attachments => We piggy backed on Deere’s current efforts with a rear quick hitch (called i-Match) that was used elsewhere. But more importantly, we leveraged some other technologies that Deere had implemented with larger tractors to create the AutoConnect mid mower deck. To connect the mower deck, you simply drove over the deck with the tractor and picked up the deck. To connect the PTO, you just turned it on. Dan Paschke was the product manager for attachments during the program. He’s largely responsible for getting these key technologies commercialized (since he first had them on a different tractor series) for the X20 program.

Reduce the effort to change attachments => We piggy backed on Deere’s current efforts with a rear quick hitch (called i-Match) that was used elsewhere. But more importantly, we leveraged some other technologies that Deere had implemented with larger tractors to create the AutoConnect mid mower deck. To connect the mower deck, you simply drove over the deck with the tractor and picked up the deck. To connect the PTO, you just turned it on. Dan Paschke was the product manager for attachments during the program. He’s largely responsible for getting these key technologies commercialized (since he first had them on a different tractor series) for the X20 program.

Work in low light conditions => Standard extra lighting to the premium model

Improve mowing performance => The 7-Iron deck that was currently only used in commercial applications was added to this residential product

Operate comfortably => Deluxe seat to the premium model with adjustable suspension. Also added tilt steer and cruise control.

Mow under trees => The roll bar, called a “ROPS” (Roll Over Protective Structure) was fixed in nearly every competitive tractor for sub-CUTs, but based on our research, we made a folding version for this tractor – taking on a significant cost increase.

Carry tools => Tool box added to the premium model

Operate safely on hillsides => Width was increased to be the widest in the industry.

For each of the features above, we concept tested these plus many more with customers – using both qualitative and quantitative techniques.

Styling

Styling – or the appearance and aesthetic design of the tractor is difficult because it is quite literally art, not science. In previous tractor projects, I felt there was room to improve on the current process to determine a design. Basically, we gave the designers suggestions – then they brought us sketches. We gave them feedback – which was highly subjective – and it continued until we felt that the styling would work for the project. However, we launched a styling study to help guide the process. We began with qualitative work to understand what descriptive words were positively associated with tractors. We ended up with a half-dozen words that described what their tractors should look like such as: functional, masculine, and aggressive. Next, we provided these “design cues” to our designers – and they provided sketches as before.

Styling – or the appearance and aesthetic design of the tractor is difficult because it is quite literally art, not science. In previous tractor projects, I felt there was room to improve on the current process to determine a design. Basically, we gave the designers suggestions – then they brought us sketches. We gave them feedback – which was highly subjective – and it continued until we felt that the styling would work for the project. However, we launched a styling study to help guide the process. We began with qualitative work to understand what descriptive words were positively associated with tractors. We ended up with a half-dozen words that described what their tractors should look like such as: functional, masculine, and aggressive. Next, we provided these “design cues” to our designers – and they provided sketches as before.

However, we could take the top design concepts and have customers rate them for functional vs. toy, masculine vs. feminine, etc. To have customers execute this, we took about 20 concepts drawn on 8.5″ x 11″ boards – and we had customers place them on a wall with a long continuum with the scale in place. There was plenty of room so that they could place them close together if, for example, a group of concepts looked equally masculine – or space them out if there was a significant difference.

The designers all participated in the research so that they not only had the scores as the output, but they had heard customer feedback first hand.

Project Challenges During Execution

The Common Platform Mistake: We challenged our directive to put all three current tractors on the same platform (the sub-CUT 2305 replacement, the CUT 2320 replacement, and the X700 garden tractor). We were not successful – and only managed to remove the X700 from the scope. For the most part, I kept my cool when navigating the project’s issues, but I became a bit frustrated when I couldn’t convince the leadership to remove the 2320 larger tractor from the project’s scope. The company had a strategy of reducing to five platforms, and there wasn’t a logical case that could be made to change their minds. I was pulled aside by one of the leaders and counseled to “let it go” and not damage my career. And…I took his advice. Not happy about it then or now. But you have to know when you’re beaten. Fast forward about a year later, and with significant engineering investment spent, it was finally proven that the modular transmission that could accommodate both the 2305 replacement and the larger 2320 replacement would not be financially feasible. As a team, we calculated what was spent going down the wrong path – and it was in the multiple millions of dollars. However, regardless, as an organization, we were able to admit that it was a mistake.

Gas Engine Investigation: We did considerable work in engineering to adopt a gas engine. We had a working model (for which I unfortunately put the wrong fuel in when testing!) that was functional and worked well. However, our market research confirmed that this would be very unpopular – and we were able to eliminate the gas SKU before it could impact the design.

Fighting for the Premium Model: Early on in the program, Deere leadership pushed against our inclusion of a premium model. The premium model would be the same capacity-wise, but would have high end features based upon our market research. It would have a tool box, a premium seat, tilt steering, a position-control hitch (allowing for more precise placement of the rear hitch), 12-V outlet, amongst other features. In my original assessment, I asserted that customers would buy one-third of the tractors with the premium features if we charged $1000 – a number that was supported with our conjoint study. Company leaders metaphorically threw tomatoes at me when presenting this concept. After all, the premium tractor couldn’t do anything that the basic tractor couldn’t do. At the time, it would have been more Deere’s style to “kit” everything. That is, create a tool-box kit. A tilt-steering kit. A deluxe-seat kit, etc. But taking a cue from the automotive industry, I knew that we could group the premium features together and drive a new, currently non-existent, premium segment of this “low margin” tractor business.

Market Share Enthusiasm: I received my greatest public rebuke when I asserted in a meeting that we would hit a very high market share number. I knew the quality of the market research that had been done – I had confidence in the team to bring it to life. I had built a model to predict market share based upon the price, competitive moves, etc. However, there were a lot of assumptions in the model and there was lots of room for error – and so there’s no doubt that it was upon a platform of both analysis and opinion that my assertion was based upon. I took a verbal beating and was forced to revise my forecasts to be more moderate in what was a personal emotional low point for me.

Pricing Pressure: Early on in the project, I was asked to raise my projected price for the project. Why, might you ask? Was it because of price moves in the market? Was it because of competitive new products? Why was I continually pressured to raise the price? It was because Deere had a certain minimum ROI that it demanded for any new project, and if I didn’t raise the price, we couldn’t achieve that minimum ROI. I found this thinking to be arbitrary – with no basis in logic. Based upon the a pricing model that I had built that predicted share based upon the price (it used the data from the many studies that we performed), I would project a price and a volume – but they were related to each other. I couldn’t bend the laws of economics any more than I could bend the laws of physics – so I stuck to my guns.

The Fat Tractor: Despite the previously mentioned styling research, when the designers (who were outside consultants) began bringing us actual models of what the tractors would look like, it seemed that they were ignoring the original directives. What was going on? It didn’t make sense. Was someone at a high level telling them to still design the tractor hood so that it could work across multiple tractor sizes? However, for more subjective design elements, such as styling, folks in some high leadership positions noted that the tractor looked fat, looked strange – and finally the design was brought in check – looking fantastic and using the styling cues from the research.

Brake Pedal Placement: The brake pedal was originally on the right side of the machine, just above the forward and reverse pedals. When testing a concept of our new tractor with customers, they complained that it was difficult to reach and that their boots could get caught underneath the brake and motion pedals. This was unfortunate because it was very late in development. However, our engineers were involved with this concept test – and heard the complaints first hand. By the time we got to the airport to travel home, they were already redesigning the brake to move it to the left side.

Phasing out of the Old Product – the 2305 tractors: We were in the last year, planning for the next year’s launch when one of my final tasks as product manager was to plan the ramp down of the previous model, the 2305. Because another company built the tractors for us, we needed very long lead times, and we would be unable to respond if we guessed incorrectly. E.J. and I suggested a slow ramp-up of the new tractors, with substantial time for testing – and that we should order 4-6 months worth of the older tractors beyond the projected launch date of our new X20 tractors. Does this seem overly conservative? Not when you first hand know all the risks involved, and all the things that must go right to launch on time. There was no slack time in the schedule, which means that to not order additional 2305 inventory was to place a bet that nothing goes wrong – and that there would be no delay. In this case, for E.J. and I, it wasn’t our decision to make – it was the factory manager for the Augusta tractor factory. The manager pointed out to me the inventory carrying costs of six months of 2305 tractors was quite expensive. I pointed out to him that missing six months of sales was 100x more expensive. I created a spreadsheet to show the magnitude of difference between six months of lost sales and six month of inventory carrying costs. From this, he told me something that I will never forget – he said that I was using “tricky math.” Well….in the end, the project launched not six months late, but a year late! The factory’s profitability took a big hit due to the manager’s inability to understand my “tricky math.”

Project Results

How did this product do in the market? Remember how I took a beating for the market share jump that I projected? The actual market share greatly exceeded even what I had predicted. By how much? Sales tripled the original estimates. Remember the premium model that was added that addressed current market needs? It ended up being much more popular than the basic unit – so in fact – we had created a new category for the premium-featured sub-CUT tractor that returns both high volumes, high market share, and high margins. I am not privy to the latest numbers, and wouldn’t share them if I had them, but a high level executive told me that it was the most successful new product that John Deere had launched in 30 years, since the gator.

Many Contributors

The X20 program is a great success and a great story. Despite this case referring to the “Deere leadership” folks who I won’t name, the team had many smart, talented people at various levels who contributed. First, we had two folks that I will describe innovation philosophers who were my counselors and teachers – John Arthur and Glenn Wright. John was our resident expert in disruptive innovation who cautioned about the errors in delivering performance beyond what customers really care about. Glenn was a master of understanding data who told me something that I’ll never forget about averages, “The average person has one testicle and one booby.” I’m not sure how you could more succinctly provide a warning about that. I’m often asked, “What’s the greatest innovation you every saw?” And my answer is not the X20 project – but one that these two led for which had the project name “Sweet Spot”. The details of that story are for another day, but I learned a ton from their execution of that project – which was truly the most impressive innovation project that I’ve ever seen.

My immediate supervisors were tremendous leaders. Tremendous. Kerri Jernigan and Brian Bauer were my bosses for most of this project. Without question, I would vote for Kerri for president of the United States. You know how they say that “people rise to their level of incompetence?” Kerri is one of the few people that I’ve ever met for whom I can’t even visualize what that level could be. She would be a fantastic CEO of any business, any size. After she was promoted out of our group, Brian took over the role from Kerri and supported our team. He gave me the time and space to analyze the market – even traveling with me as I did market research. He’s a solid dude who nurtured our team to success. He liked the pricing model that I built – and as an engineer – I think that he appreciated that I tried to make all the decision-making as scientific as possible.

Dave Knight was the director of engineering for compact tractors. He encouraged experimentation – and didn’t kill anyone when we spent a few million dollars investigating a modular transmission approach that ultimately wasn’t going to work. Super guy who anyone would love to work for.

I mentioned John Kuhn already as the technical lead. Patient, smart, experienced – knows everything that can be known about mowing.

Additionally, Dan Paschke was the leader of the attachment strategy – and ultimately – it was an attachment innovation – the drive-over mower deck that was the biggest “wow” feature of the tractor. Dan also took over the marketing and launch efforts after I departed Deere – and the results speak for themselves.